|

Environmental Pressures

Non-native invasive species: The introduction of non-native plant or animal species brings the risk of competition or disease for our native biota. Unfortunately rivers can act as natural corridors for the dispersal of some of these invaders. For example:

-

The Japanese knotweed, Fallopia japonica, first became  established in Britain in South Wales. This extremely aggressive plant can completely replace native vegetation on riverbanks and grow through concrete. Cutting and the use of herbicides have had little effect on its spread. established in Britain in South Wales. This extremely aggressive plant can completely replace native vegetation on riverbanks and grow through concrete. Cutting and the use of herbicides have had little effect on its spread.

-

The American signal crayfish, Pacifastacus leniusculus has escaped from commercial farms and it competes with the increasingly rare native white-clawed crayfish Austropotamobius pallipes. It also carries a fungal disease called crayfish plague, which is fatal to native crayfish.

-

Mink have also been introduced from North America and frequent riverside habitats. Attempts to control their distribution and numbers have proved futile. The increase in mink populations has been strongly linked with a decline in the endangered native water vole population.

Pollution - “Acid Water”: Welsh rivers are still recovering  from a long history of metal pollution, mainly from lead and zinc mines, some of which are pre-Roman in origin. In the soft waters of west Wales these metals are especially toxic to invertebrate life and fishes and they continue to leak from abandoned mines. from a long history of metal pollution, mainly from lead and zinc mines, some of which are pre-Roman in origin. In the soft waters of west Wales these metals are especially toxic to invertebrate life and fishes and they continue to leak from abandoned mines.

-

One of the earliest water pollution indices based on the distribution and abundance of invertebrates in polluted and non-polluted reaches was developed on the Afon Rheidol, mid-Wales.

-

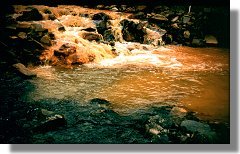

The Afon Goch (meaning Red River), which drains the currently inactive copper mine on Parys Mountain, Anglesey, has been described as one of the most acid- and metal-contaminated streams in the UK. Its degree of acidity is close to vinegar!

“Acid Rain” – the forgotten environmental issue

When fossil fuels (e.g.coal) are burned, the gases produced combine with water in the atmospheric to fall as “acid rain” or dilute forms of sulphuric and nitric acid. In addition, road traffic produces about 50% of the nitrogen-derived pollution.

-

Although water is naturally slightly acid, the geology of Wales with a predominance of acidic rocks makes its freshwater habitats very vulnerable to increased amounts of “acid rain”. The natural biodiversity of streams is impacted with changes in compositon and abundance of plant and animal species. In addition, aluminium and other metals that are leached from surrounding soils can be toxic to fishes and their eggs.

-

When compared with England and Scotland, Welsh waters have been the most seriously damaged by acid rain, including the loss of several populations of native brown trout.

-

Over the past 25, years polluting emissions from power stations have been greatly reduced. Now ecologists can detect some signs of the chemical recovery of the acidified headwater streams but few signs of biological recovery.

-

Various attempts have been made to reverse the effects of “acid rain”. For example, lime has been spread on the surrounding land or added directly to the water. This action will secure temporary treatment of some of the symptoms.

“Sheep Dip”

It is estimated that there are in the range of 8-9 million sheep in Wales. Their detrimental impact on upland environments is not confined to overgrazing, as they cause and accelerate erosion with the sediments being washed into streams. Soils compacted by hooves have greater water run off, with increased flooding possible downstream. It is estimated that there are in the range of 8-9 million sheep in Wales. Their detrimental impact on upland environments is not confined to overgrazing, as they cause and accelerate erosion with the sediments being washed into streams. Soils compacted by hooves have greater water run off, with increased flooding possible downstream.

-

In addition all these animals require regular treatment by dipping for skin parasites. The chemicals used are formulated to be fatal to invertebrates so any releases into fresh water have serious consequences for aquatic insects.

-

Out of a concern for human health risks, in 2006 organophosphate sheep dips were replaced by synthetic pyrethroids. However, it was subsequently found that very small amounts (a single dripping sheep!) of the cypermethrin sheep dip could be fatal for aquatic invertebrates along hundreds of metres of streams.

-

The sale of these toxic chemicals has been suspended but it has been estimated that over 1000 km of stream have been impacted by sheep dip in Wales. Moreover, other chemicals are now being monitored for environmental impacts – for example, the concentrations of oestrogenic compounds (from human contraceptive pills) found in sewage outfalls has produced “intersex” fishes, that is, male fish with some internal female characteristics.

Removing the barriers: Although the water will still flow down  the river, the installation of physical barriers, such as weirs, can prevent the free movement of migratory fishes to their spawning grounds. The ideal option is to remove these structures completely but this is not always possible. In some cases they are necessary water level control features appreciated for archaeological or scenic reasons. the river, the installation of physical barriers, such as weirs, can prevent the free movement of migratory fishes to their spawning grounds. The ideal option is to remove these structures completely but this is not always possible. In some cases they are necessary water level control features appreciated for archaeological or scenic reasons.

-

Ingenious engineers can design “fish-passes” which replace the single, large drop in water level with a stairs of small pools, which are easily traversed by the fishes. These structures are installed into or placed alongside the original barrier.

-

Since the mid-1990s, fish passes restoring access to hundreds of kilometres of previously used territory and spawning grounds have circumvented more than ten major weirs in Wales.

Read more in The Rivers of Wales

|